Introduction to the CFDI Therapeutic Model

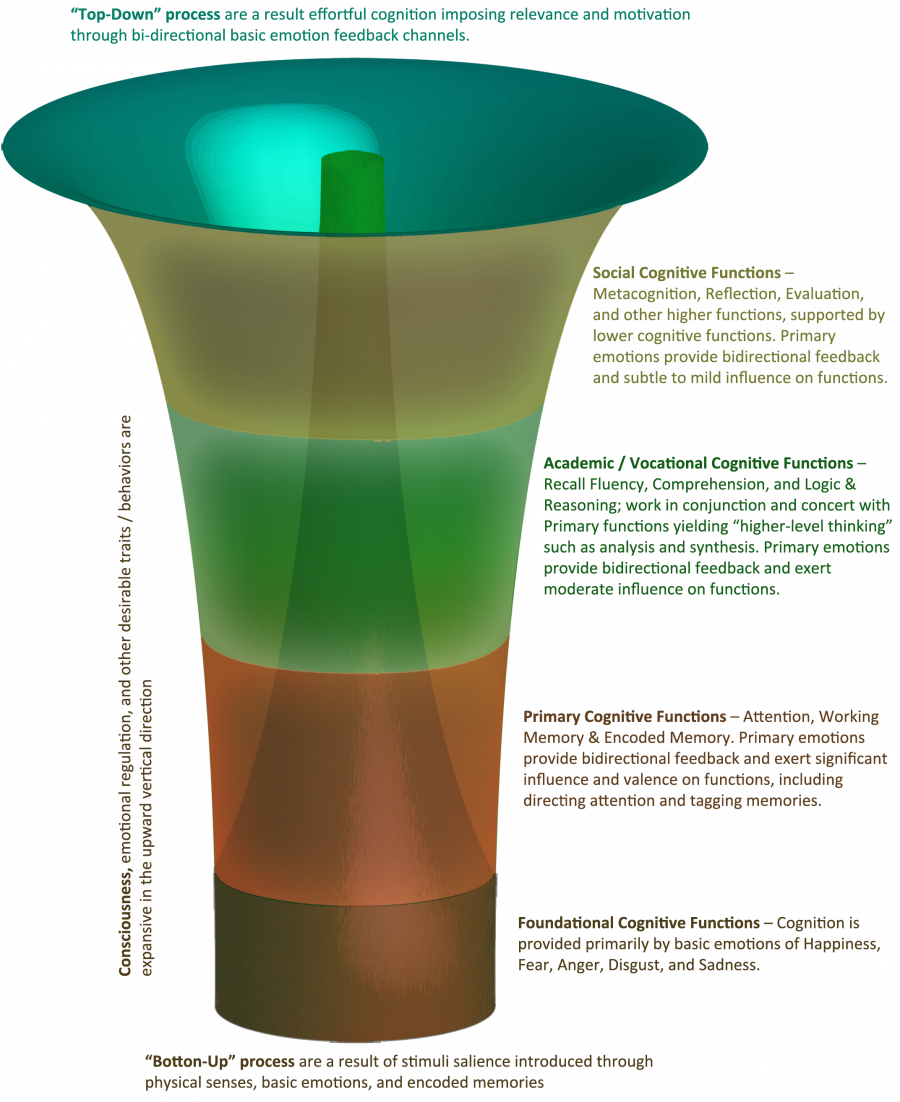

The CFD Institute promotes cognitive function development therapy based on a unified model of basic or primary cognitive functions upon which all other cognitive functions and higher-order processes depend. From this perspective, all therapeutic procedures will necessarily exercise the primary functions. However, those activities which target, stimulate, develop, and integrate these primary functions have been shown to have the greatest efficiency in terms of achieving therapeutic goals, and are understood as foundational to CFDT’s long-lasting, far-reaching, transferable results.

The three primary cognitive functions of the therapeutic model are attention, working memory, and encoded memory. Within the therapeutic model, attention and memory are inextricably linked, being composed of overlapping web-like networks that utilize many of the same neural resources and structures. [1] [2] Empirical research indicates that both attention and memory rely on the various sensory cortexes, both for stimulus input and for short term information storage. [3] [4] [5] [6] Thus, on the outermost portion of the therapeutic model, we include representation of the various sensory cortexes. These are to be understood as being separate structures at various locations throughout the brain, but as being included within the attention / memory neural network.

Working memory is conceived of as being the functional overlap of attention and encoded memory. That is, there are no discrete brain structures dedicated to the existence and exercise of working memory. Rather, working memory arises as attention is devoted to information flowing into and out from encoded memory. Moreover, information stored and processed in working memory is encoded as neural oscillations. For therapeutic purposes encoding within the gamma frequency range is of most importance, and oscillations in the theta frequency (serving as carrier waves) are of also of interest.

It should be noted that an individual's ability to process information (i.e. the working memory function) is strongly tied and independently dependent on bi-directional neural interaction with the attention networks and encoded memory systems. That is, unless the individual has the cognitive resources to attend to information encoded in working memory, the neural oscillation will rapidly decay and the information will be lost. Likewise, processing of information selected as relevant by the attention system depends on working memory’s ability to receive copies of related information from the various memory systems. Without similar information in memory to support working memory computations, efficient processing requires attending to detail and process accuracy. With similar information already present and readily available from encoded memory, efficient processing manifests as processing speed. For example, a child only recently introduced to addition will appear to work slowly and laboriously to determine the sum of two numbers. That same child's ability to correctly multiply two numbers - even if the calculation is within the child's capability - will most likely require direct guidance and the child will not readily understand the results. However, ask a child who is well-versed with multiplication to add two numbers and efficient processing will be determined by the speed with which the child gives the sum.

Generally speaking, the three primary cognitive functions behave as a single, transcranial “neural-web” of inextricably interconnected, mutually dependent subnetworks. Of therapeutic importance is to recognize that these functions operate in unison, may have differing relative strengths, and require the efficient coordination and integration of multiple discrete brain structures (one of the purposes of theta band neural oscillations). A significant portion of therapeutic procedures will, therefore, be designed to target and develop the capacity, integration, and efficiency of the functions and their sub-networks as appropriate to achieve therapeutic goals. Thus, stimulating and developing the three primary cognitive functions will be a staple of most, if not all therapeutic sessions. Depending on the therapeutic plan, however, additional time each week or each session can be devoted to working with the client on secondary or tertiary cognitive functions, or even on higher-level processes. Development of procedures to address these functions and procedures will be dependent upon client abilities and outcome goals, and will thus be developed on a case-by-case basis.

Citations

- ^ Moore, Davis R., et. al. (November 26, 2015). “The Persistent Influence of Concussion on Attention, Executive Control, and Neuroelectructric Function in Preadolescent Children.” International Journal of Psychophysiology. vol. 99, pp 85-95. Article Link.

- ^ Fougnie, Daryl (2008). “Chapter 1: The Relationship between Attention and Working Memory.” Conference Proceedings Article Link.

- ^ Taylor, Joathon G. (2008). “On the Relationship between Attention and Consciousness.” Conference Proceedings. Article Link.

- ^ Sarter, Marting, et. al. (2001). “Cognitive Neuroscience of Sustained Attenion: Where top-down meets bottom-up.” Brain Research Reviews . vol. 35, pp 146-160. Article Link.

- ^ Barton, Brian and Alyssa A Brewer (June 12, 2019). “Attention and Working Memory in Human Auditory Cortex.” IntechOpen. Chapter Link.

- ^ Moss, Andrew, et. al. (2019). “Olfactory Working Memory: Exploring the differences in n-back memory for high and low verbalizable oderants.” Memory. Article Link.